First Impressions of Baja, Mexico

A week driving the peninsula

As I settled into my beach chair with a bowl of freshly-cut papaya, a puff of air broke the silence. It was the same sound made when a snorkeler blows through their mouthpiece to clear out water, but no one was swimming in the placid inlet of Laguna Ojo de Liebre. It could only be one thing: a whale’s breath.

I scanned the glassy green water and saw the back of a gray whale break the surface. I went to the van to grab my binoculars. The whale waved a flipper; its tail broke the surface. I was about two football fields distant, and I watched it for a while, lolling in the water, rolling on its side, the periodic puff of its blowhole audible from my campsite in the dunes.

Within an hour, the tide came in, the wind made ripples then waves that drowned out the whale blows, and the cetacean swam away. I can still see the spray of distant blowholes from some of the other hundred or so gray whales that winter in the Vizcaino biosphere reserve just south of Guerrero Negro. In a few weeks, nearly a thousand gray whales will complete their journey from the Bering Sea to mate and give birth in this lagoon. I took a boat tour in a small panga when I arrived, and one whale came close enough for the guy sitting behind me to pet its forehead.

For the two days since then, I’ve been camped in the dunes next to the lagoon doing nothing but watching tides rise and fall while ibis and gulls forage in the mud flats. The mornings are quiet and calm, then the wind picks up about 10:30am and blows until sunset. If I position my chair just right, the few surrounding campsites are obscured by dunes and my van, and it’s like having a deserted beach all to myself.

I hadn’t planned to stay more than one night—the best beaches in Baja are further south. But after two months on the road, I desperately needed a down day. Or two. Freezing temperatures chased me south from New Hampshire at the end of November and followed me across Arkansas, Texas, and New Mexico. I had to keep moving so the pipes in my camper wouldn’t freeze. By the time I reached Arizona and Southern California, nighttime temperatures stayed reliably in the 40s, but there was so much to see and do along the way that I never had the time to sit still (except for one morning when the Santa Ana winds immobilized traffic on the interstate and I holed up in my van off of I-10).

So I’ve stayed on the shores of Laguna Ojo de Liebre (Hare’s Eye Lagoon) a few extra nights, sitting in the sun, blocked from the worst of the wind, as puffs of dust collect on my iPad and my chair and my dogs, then stick to our feet and find their way onto my carpet and bedspread.

With nothing better to do, I thought I’d collect my first impressions from a week in Baja, traveling from the Arizona border at San Luis through the Mexican state of Baja California into Baja California Sur.

Border Crossing

The most nerve-wracking part of the whole trip was crossing the border into Mexico. I spent weeks debating which crossing to use, on which day of the week, at which time of day, and researching what I could and couldn’t bring with me. I timed my grocery shopping to empty my fridge of produce before crossing, lest I be detained for a stray banana. I stayed up till 2am the night before, digging through every drawer and cubby of my 1999 Roadtrek camper van to remove anything valuable or suspicious (personal safety devices like mace are illegal in Mexico). I organized cash, credit cards, and my passport into one of those touristy under-your-clothes waist belts, with a stash hidden in a secret compartment of my van. I tucked away my prescriptions, electronics, and anything else that might attract an inspector’s attention. I installed seatbelts for my dogs to restrain them if my van was searched.

When I finally arrived at Mexican customs in San Luis Rio Colorado at 3pm on a Tuesday—much later than planned, thanks to some last-minute van repairs and Amazon returns in Yuma—crossing was a non-event. In most of the lanes, cars with Mexican plates appeared to drive right through without stopping. That didn’t seem right to me, so I voluntarily selected the lane to declare stuff (not knowing if I had anything to declare). A young kid in a customs uniform poked his head in my van, peeked in my fridge, and made no comment about the stray avocados I’d forgotten to throw out. I asked him where to go to get my FMM—the Forma Migratoria Múltiple—a stamped piece of paper that would allow me to stay up to 180 days in Mexico. I parked and walked to the building, where a sharply-dressed guard with her hair in a bun opened the door and showed me to the counter. A steady line of Mexicans streamed through the pedestrian crossing, presumably on their way home from work, school, or shopping on the American side of San Luis (it felt like one city, divided in half by the border wall). An agent took my passport, filled out the form, and sent me next door to the bank to pay. I then returned with my receipt and got my passport and FMM stamped. As I drove away, I felt like surely I’d missed something—didn’t they want to inspect my animals or hassle me over my forgotten fruit? But I rolled down the streets of San Luis, away from the iron border fence, with barely a glance from the fatigue-clad, machine-gun toting young man whose face was covered with a camouflage bandana.

Safety

My primary concern after crossing the border into Mexico was safety—specifically, whether I would be kidnapped or killed. Border towns in Mexico are notoriously dangerous, with drug cartels exerting control over local governments and murdering anyone who gets in their way. I knew enough about the cartels from watching Ozark on Netflix that I wanted to get away from the border as quickly as possible. Unfortunately, towns along both of the main routes south into Baja had been in the news for high-profile violence. On the west coast, three surfers were murdered outside Ensenada last year when some thieves tried to take the tires from their vehicle. Along the Gulf of California, there had been several recent cartel-related murders in the quiet expat city of San Felipe. From what I read on Facebook, a local official wouldn’t bend to the cartel’s wishes, so they shot his sons at their restaurant on Christmas Eve.

I locked my doors as I navigated the streets of San Luis Rio Colorado, and soon I’d made it to the US State Department-sanctioned route that traced the outskirts of Mexicali before heading south. Dwellings along the highway were pieced together from scrap materials. I counted three dead dogs on the side of the road after I exited the highway, and when a pickup passed me, a spray of blood and feathers splashed on my windshield—the remnants of a feral chicken? I made a note-to-self to find a car wash once I made it to Baja California Sur.

With my later-than-planned border crossing, I had less than two hours of daylight, so I opened my iOverlander app and found a safe-sounding campground just off the highway on a riverfront property owned by American expat Don Thousand. Rancho Mil was the perfect stopover. A mile-long dirt driveway took me through a locked gate to a campsite on the banks of the Rio Hardy, which used to be a part of the Colorado River before a century of dams and drainage ditches altered its flow. White pelicans glided along the riverbank as the sun set behind the Sierra Mayor, a perfect panorama of river and mountains.

My sense of safety was short-lived when I connected to WiFi and read in a Baja Facebook group that two bodies had been dumped around Kilometer 75 of Highway 5 the week before. In the morning I asked Don where that was. “Just down the road,” he told me nonchalantly.

The American expats I’ve spoken to seem largely unconcerned about the violence, which they say targets people who get in the way of the cartels. “They don’t want to scare the tourists,” Don explained. “Some of the cartels own hotels and other businesses that benefit from tourism dollars.” Elsewhere on Facebook I’d read that the US government’s recent murder of a cartel boss had set off turf wars between rival gangs. The consensus seemed to be that San Felipe was safe now, due to an increased military and police presence since the murders a month earlier.

I spent my second day in Baja driving as far south as possible. I had to stop in San Felipe for groceries, since I’d dutifully emptied my fridge for the crossing. Everything seemed like business as usual at the Calimax grocery store, where I got pesos from the ATM and replenished my stock of avocados and bananas. Billboards advertised RV parks and vacation rentals in English for American expats and tourists. I glimpsed the emerald waters of the Sea of Cortez for the first time, but I bypassed the beaches. My destination was Bahía de Los Angeles, a quiet seaside town 200 miles south and 40 miles off the main highway.

Driving south from San Felipe, I encountered my first real safety concern in Mexico: the roads. Highways near the border could have almost passed as American roads, but just past the last of the weekend-expat enclaves, Highway 5 got sketchy. Breakdown lanes ceased to exist, and the highway narrowed to 19 feet total width, with a sharp dropoff at the edge of the white line on either side. Giant potholes appeared out of nowhere, in the middle of my lane, in the middle of the oncoming lane, or straddling the center line. They could mostly be avoided when traveling at a modest speed with no oncoming traffic, but things got scary when a semi truck approached, and I hoped we didn’t meet where there was a hole for them to dodge. I stuck strictly to the speed limit, which alternated between 60 and 80 kilometers an hour, or 35-45 miles per hour. Even this was too fast on the worst stretches of road. It was five hours of white-knuckle driving, but the scenery made the trip magical in spite of the road conditions (see the Landscape section below!).

I made sure to heed the other safety warnings I’d read about traveling in Mexico:

1) If you see a gas station, stop and top off your tank. There can be long stretches without services, and sometimes the only station for a hundred miles will be out of gas. I filled up my van and my spare 5-gallon gas can in San Felipe.

2) Make sure the gas pump is zeroed out before the attendant starts pumping. Most gas stations in Baja are full-serve, and I’d heard that some of the attendants will neglect to zero out the pump, leaving an unsuspecting Gringo to pay extra, with the attendant pocketing the difference. My attendant in San Felipe pointed out the zeroed pump to me before she started.

3) Act like a tourist at military checkpoints. Mexico has official (and sometimes unofficial) roadblocks where armed soldiers stop vehicles. Camper vans like mine are frequently searched, and some gringos get caught with drugs (all of which are illegal in Mexico, including marijuana). Police are known to extort hefty bribes if they catch you breaking a law. Besides not carrying contraband in the first place, playing the role of the dumb tourist is apparently the best way to avoid hassles. Even if you know some Spanish, act like you don’t, I was told. I smiled, stared at the soldiers with a blank look on my face, responded “yes” when they said “Tourist?” and said I was going to Cabo. Each time, they waved me along. Baxter barking in the passenger seat probably helped expedite the process (I’ve noticed Mexicans are wary of dogs, probably due to the ubiquity of strays roaming the streets).

4) Don’t draw attention to yourself! Drive the speed limit, obey the laws, don’t wear flashy clothes or jewelry or anything else that could make you a target. The night before crossing the border, while camped in a Planet Fitness parking lot after a coveted gym shower, I removed my Liz Explores magnets and tire cover from the van. I didn’t want people thinking I was some famous YouTuber with lots of money and fancy equipment. I definitely feel better driving my 1999 Dodge van than I would in a new Mercedes Sprinter (though there are plenty of those in Baja, too).

Landscape

Once I made it south of the border, the scenery was breathtaking all the way to Bahía de Los Angeles. In the course of a couple hundred miles, I passed through barren salt flats ringed by rocky volcanic peaks, skirted a cliff high above the Sea of Cortez, and wound my way through a cactus forest of cordon, boojum, and elephant trees. I texted a friend to say that it felt like driving through Big Bend, Joshua Tree, and Saguaro National Parks, plus the Pacific Coast Highway all in one. Coming from the East Coast, I love the ocean and the mountains, but I’ve always lamented that they’re separated by several hundred miles. No so in Baja. The potholed road to Bahía de Los Angeles spilled out into a vista of ocean, islands, and mountains. I needed to keep pinching myself to make sure it was real. I’ll let the images speak for themselves:

Wildlife

The Sea of Cortez, which separates the Baja peninsula from mainland Mexico, is known as “the world’s aquarium.” Humpbacks, gray whales, and whale sharks spend their winters here, along with hundreds of migratory and endemic birds. Hours can be passed just watching pelicans dive, ospreys skim the surface, and ibises poke their long beaks into the sand. One night I listened to coyotes howl outside my van window; in some places they’re known to wander into camp. When I reach the warmer waters further south, I look forward to snorkeling and scuba diving, paddling along the coast, and exploring marine environment. My original major in college was Marine Biology before I switched to Environmental Science, so I’m excited to geek out on my coastal ecology!

Climate

After spending two months in the zero-percent-humidity of the Chihuahuan, Sonoran, and Mojave deserts of the southwestern US (and obsessively washing and hand-sanitizing everywhere I went), my fingers were cracked and bleeding so painfully that I wore rubber finger-gloves just to survive the day. Within 24 hours on the coast of Baja, my wounds closed up and the Band-Aids came off. The digital thermometer in my van shows 60% humidity here, which feels just about perfect.

I’m finally able to slow my pace because I left behind below-freezing nighttime temperatures when I crossed the border. The northern parts of Baja have a climate similar to San Diego, with a couple weeks of cold nights in January but almost never below freezing. I’m about halfway down the peninsula now, and nighttime temperatures are in the 50s with daytime highs around 65 or 70. It’s perfect, except for…

THE WIND! In the comments section of my post about California’s Santa Ana winds, someone warned me of the El Norte winds in Baja. On the coast, the mornings start out calm, but the wind picks up around 10:30am and blows all day until sunset. I don’t yet know if this is a constant thing in winter, or if it comes and goes, or if it’s worse in some places than others. All I know is that most afternoons, the wind makes it uncomfortable to sit on the beach, because it cools the air so much, and because you get sandblasted. Some days are worse than others, but every day I’ve been on the coast, it’s been a thing. I’m hoping there will be some protected beaches further south so I can sunbathe without a jacket.

And I have been wearing my puffy jacket daily, in the hours before the sun warms the air, and in the afternoons when the wind picks up, and in the evening when it cools off again. So far my daily wardrobe has been pants and a long-sleeved shirt, except for one afternoon in downtown Guerrero Negro. I started sweating setting up camp, so for a couple hours I changed into shorts and a t-shirt and turned on my air conditioner.

It hasn’t been as sunny here as I’d imagined; most days are a mix of sun and clouds, with some more cloudy than others. A couple nights ago I saw rain on the horizon, somewhere in the Pacific. A 60-degree day can feel 75 if it’s sunny and then feel 45 if the clouds roll in and the wind picks up, so layers are key. At least I haven’t had to slather up with sunscreen.

My husband Seth keeps sending screenshots of 18-below-zero Fahrenheit mornings in New Hampshire, so I can’t complain about some clouds and wind!

People

Everything I’ve read says that the people in Baja are friendly and helpful, and that’s proven to be true for me so far. I’ve had fun practicing my Spanish with Mexicans who don’t speak English, and they’ve been patient and accommodating. When I arrived in Guerrero Negro, I spent a Sunday morning seeking out a car wash (remember the feral chicken incident?). The first two were closed, but the third one had three men waiting to help me. They quoted me 200 pesos (about $10) to wash my furgoneta (I quickly looked up the Spanish word for van), and I sat in the driver’s seat doing research on my phone while they spent an hour scrubbing and detailing the exterior, roof, and undercarriage by hand. When I asked for help finding an agua purificada station to fill my van with drinking water, one of them jumped in his pickup truck and led me there. Then the agua purificada guy joked around and told me about the best beaches to visit near Mulegé.

My fellow tourists are friendly, too, and eager to swap stories or recommend places they’ve been or plan to go. They’ve also been able to help out in a pinch. When the wind picked up this morning, I was cranking in my awning when the 26-year-old sun-baked plastic snapped. A German couple walked by while I was trying to reel it in one centimeter at a time with a pair of pliers. I asked if they could help, and then I flagged down an Austrian couple a few minutes later, and with three of us ladies taking the weight off the awning and the two men improvising a new crank, we were able to get it closed. (Sadly, I won’t be able to deploy the awning again until I can replace this ancient part, who knows when.) If they hadn’t come along, I might have been driving to Mulegé with a horizontal sail sticking off the side of my van.

Language

Thank goodness 18-year-old me had the foresight to minor in French and Spanish in college. I never became fluent, but I reasoned that if I could speak and understand English, French, and Spanish, I could converse with about half the world’s population.

That was twenty-five years ago, though, and I haven’t used it since. A month ago I downloaded the Duolingo app and took the upsell for ad-free Spanish lessons. Every night after I tuck myself into the back of the van, I do a five-minute lesson before falling asleep (sadly, this requires internet, so it’s been harder to keep up with now that I’m actually in Mexico). I’ve managed to communicate surprisingly well, finding ways to ask or explain most things. I use Google Translate to find words and phrases I’ve forgotten. It’s been an unexpected joy of this trip to rekindle my love of languages, and to have real conversations with non-English-speaking Mexicans.

I’ve started suggesting to people (in Spanish) that they speak to me as if I were a three-year-old girl: slowly, and using simple words. I can only catch about 10% of a conversation between native speakers, but when someone speaks to me directly and I ask clarifying questions, we usually get the point across.

Nonverbal communication is also surprisingly effective. It’s usually possible to point or demonstrate what you’re trying to say. My dogs are an excellent example of this: when they are hungry, thirsty, want pets, or need to go out, they make themselves perfectly clear by barking at the dog food cabinet, pawing at the empty water dish, nudging my hand, or wagging their tails at the door. I can usually make my point in a similar manner if all else fails.

I’ve found Mexicans to be particularly indulgent of my desire to practice their language. When I studied abroad in France, my nearly-impeccable French would usually generate responses in English, which hindered my efforts to gain fluency. Even English-speaking Mexicans have been patient enough to let me work through what I’m trying to say and respond in their native tongue. Most campgrounds and tourists establishments have personnel who speak English, so traveling without speaking any Spanish is definitely doable.

Camping

I’ve only been here a week, but so far the camping in Baja has been amazing. The peninsula is remarkably undeveloped. Any American coastline this beautiful would be lined with high-rises and resorts; not so throughout most of Baja. Much of its thousands of miles of coastline is public, and in many places you can pull your van right up to the beach. Established campgrounds cost between $5-15 per night, depending on the location and services. In some places it’s worth the price for the added sense of security (plus a hot shower). Other beaches have popular boondocking spots where you can park for free, usually with some fellow travelers nearby. Everywhere I’ve camped so far has felt completely safe.

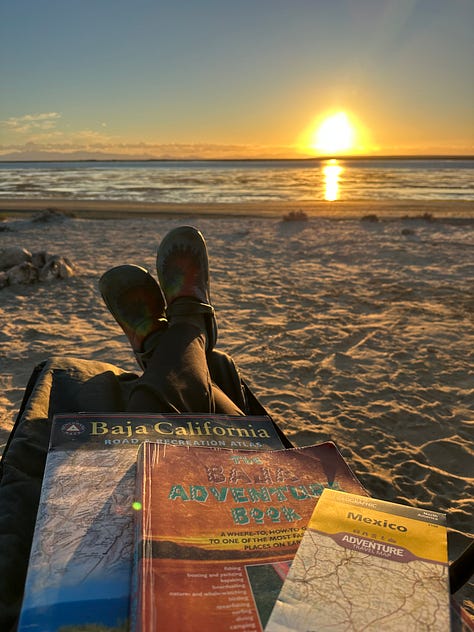

Sunrise and sunset are the highlight of every day. The transpeninsular highway winds back and forth between the westward-facing Pacific and the eastward-facing Sea of Cortez, so every day I’ve been able to enjoy either sunrise or sunset over the ocean. It doesn’t get much better than this:

Cost

Not everything in Mexico is as cheap as I’d hoped, but it’s remarkably affordable. I asked an expat how the cost of living compared overall to the average in the US, and she said it’s probably 30% cheaper to live in Mexico.

The biggest expense is gas, which averages around $5.50 a gallon (I still haven’t done the math to convert pesos per liter to dollars per gallon, but this is what I was told). Eating out at establishments catering to tourists is only slightly cheaper than in the States (I have twice ordered something simlple, like chips and guacamole or avocado toast with fresh-squeezed lemonade, and it’s cost about $10). Groceries seem significantly cheaper, depending what you buy—maybe half of what you’d pay in the States (unless it’s a specialty or imported item). Campgrounds are less than half of what they cost in the US, and some offer full hookups.

The tradeoff, of course, is that availability of certain things is limited compared to the US. I tried to stock up on speciality grocery items before I crossed the border—things like veggie burgers, almond milk, tofu, trail mix, and granola bars, since small-town Mexico is not the most vegan-friendly. I’ve been purchasing produce locally, of course, and disinfecting it in a solution of Microdyn, available in every grocery store. (Other travelers and expats I’ve spoken to don’t do this and haven’t had any gastrointestinal issues, but I’d rather not take my chances.)

Tourist stuff seems to cost what tourist stuff costs. I’ve only done the gray whale tour so far, which was $65 for two hours—enough that I’ve been reluctant to take a second trip. They also wanted payment in cash, preferably US dollars. I don’t typically spend much on organized tours, but I’ll try to budget for a few more unique experiences like that.

Challenges

Van life in Baja is an adventure, for better and for worse.

One of the biggest challenges is the ubiquity of dust and sand—it seeps into every crack and crevice. Moments after opening my iPad outside, the keyboard was gritty and the screen was coated in a fine layer of dirt. The dogs track sand in and out of the van all day long, especially after they’ve been lying on the beach (and despite my best efforts to wipe it off). Following the awning incident earlier today, I moved my office inside the van, and there is somehow still a fresh layer of dust on the tabletop and the screen of my iPhone. It’s also coating the windows of my freshly-cleaned rig.

The challenges of driving, wind, and language barriers have already been discussed, but they are worth mentioning again, because they come up day after day.

Connectivity is the other big issue. Before crossing the border, I paid $100 for two months of unlimited internet using the Mexican eSIM company Holafly. I spent several hours in a parking lot in Yuma figuring out how to install and activate the eSIM on my phone, and now it works great—IF I have a good cell signal. Most of the 500 miles I’ve traveled so far have had zero signal. When I do have cell coverage, I can make and receive calls on my Spectrum phone plan; I pay an extra $10/month for unlimited international talk and text.

Luckily I have offline access to Apple Maps (I downloaded Baja before I left) and iOverlander, the app I use to find campsites. So I’m able to figure out where I’m going and how to get there, even without the internet. Everything else I need the internet for has to happen in the brief hours I spend in a city (with cell service) or a cafe (with internet)—calling home, checking the weather, reading the news, researching travel stuff, and keeping my streak going on Duolingo. I make lists of internet things I must do, and when I get service, I’m trapped there until I get them all done. I haven’t been able to keep up with backing up my photos to iCloud; the connection at the cafes I’ve visited has been too slow to upload the number of photos I take in a day, let alone multiple days. I try to get my phone backed up once every week or two, just in case.

The solution to the connectivity problem would be to invest in Starlink, Elon Musk’s satellite internet company. There is now a mobile version for use in RVs. The problem is that 1) the equipment and service are expensive; 2) I’ve heard it uses a lot of battery power, and I don’t have much; 3) from what I understand, you have to set it up and put it away everywhere you go—and that means having a place to store the panel inside your van (I have occasionally seen them roof-mounted, but I’m not sure that’s the best idea?). And also, you’re giving money to Elon Musk, which doesn’t feel so good to me these days.

I’ve heard that Starlink is cheaper if you buy it and set up your service while in Mexico… like $75/month instead of $150/month, and the receiver might be $350 instead of $500-600? It’s tempting. But for the most part, I don’t mind being off-grid for a couple days at a time. I have a Garmin InReach Mini GPS device that, in theory, I can use to text my family that I’m alive, though when I took it out today it wouldn’t pair to my phone. When it works, that’s really all I need.

My other main challenge when it comes to boondocking (i.e. camping on a beach without an electric hookup) is that my RV battery only lasts a couple days, even when I use it minimally for lights and phone-charging. Before I left the States, I looked into installing a couple hundred watts of solar on my Roadtrek, but I didn’t have time to get it done before the trip. That will be a priority when I get back, because the alternative is that I have to either run my loud, stinky generator or idle my loud, stinky van for a few hours every couple days to charge my battery (if I’m not driving between destinations or plugged in at an RV park). And that’s not the best way to make friends on a beautiful beach in Baja.

Advantages

So far, the advantages of visiting Baja absolutely outweigh the challenges. It’s incredibly beautiful and remarkably affordable. Most areas are undeveloped and not at all touristy. There’s so much freedom in being able to camp—for free!—on any number of gorgeous beaches. I have a million-dollar view every night. No matter where I am, there’s a beautiful sunrise and sunset. The pace of life is peaceful, relaxing, and restorative. And best of all, I can have my dogs on the beach—something almost unheard of in the US.

The challenges, the remoteness, the language, the culture, and the landscape all make travel in Baja a true adventure. It’s my kind of place.

Conclusion

I’ve only been in Baja for a week, so these are just my first impressions. I wanted to get my thoughts on the page while they’re fresh, because after I’ve been doing this for a month or two, the newness will fade.

Now it’s time to go enjoy one of the biggest perks of Baja life—a sunset beach stroll with Baxter and Laney!

This was so fun to read while drinking my morning coffee. You are so inspiring and so brave. I went to Baja when I was a kid, and it was beautiful!

You had me at whale sharks.... if you get a chance to swim with them, I need every detail! 😍

Liz! I got on! Nice spots! So glad the border and early miles in went well! Joyce from Quartzsite