Into the Wild

Following the footsteps of Chris McCandless

Christopher Johnson McCandless died 15 miles from where I am now camped, 31 years ago to the day, lying on a dirty cot in an abandoned Fairbanks city bus next to the Susitna River.

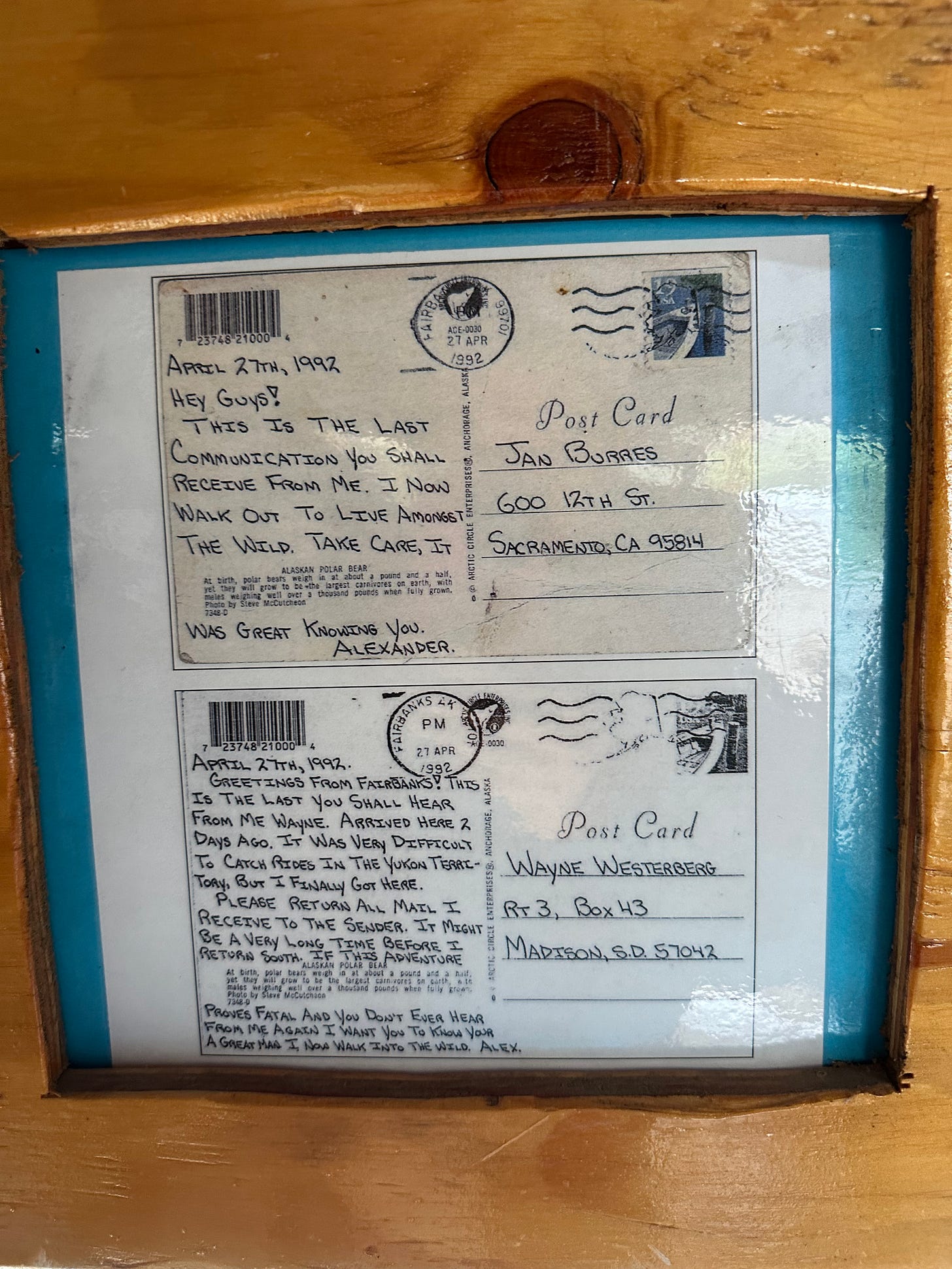

It was August 1992, and Chris had been living in the Alaskan wilderness on his own since the end of April, when he’d hitched a ride to the start of the Stampede Trail with Jim Gallien. Jim had pleaded with Chris to wait until later in the spring to embark on his Thoreauvian experiment, then offered him his own rubber boots and sandwiches when Chris insisted he must go. Jim snapped a photo with Chris’ camera as the 24-year-old shouldered his rifle in the open tundra at the end of the Stampede Road. “I NOW WALK INTO THE WILD” were Chris’ iconic parting words to civilization, penned to his friend and former boss Wayne Westerberg on a postcard of a polar bear. “IF THIS ADVENTURE PROVES FATAL AND YOU DON’T EVER HEAR FROM ME AGAIN I WANT YOU TO KNOW YOUR (sic) A GREAT MAN,” he told Wayne, acknowledging his acceptance that following his dream could lead to his demise.

We know Chris’ story in detail because journalist Jon Krakauer followed the breadcrumbs of Chris’ travels in the early 1990s, culminating in a 9,000-word Outside magazine article in 1993. Krakauer’s voluminous research then spilled over into his 1996 book Into the Wild. The tale caught Hollywood’s attention and became a feature film in 2007, starring Emile Hirsch.

I discovered the book Into the Wild in 2007 when I was a first-year PhD student at the University of Wisconsin, toiling 18-hour days through 500-page academic treatises on environmental history. I don’t remember how I fit in pleasure reading; maybe during the winter break, feeling trapped and overwhelmed by the demands of my first semester and longing for escape? I was captivated by the story of this young man (I was just 27 at the time) who, upon graduating Emory University in Atlanta, had given away his $24,000 trust fund to Oxfam and set out on a two-year odyssey across the North American continent. Within a few weeks, Chris ditched his car, burned the rest of his money, and went on foot, hitchhiking and train-hopping his way through the American Southwest, then illegally paddling a kayak all the way down the Colorado River to the Sea of Cortez in Mexico. He made his way to South Dakota, where he found work on a grain farm with Wayne Westerberg to save money for his final push to the Alaskan frontier.

I’d always had an insatiable wanderlust, even as I dutifully worked my way to a 4.0 GPA, graduating valedictorian in high school and then summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa in college, with a double major in Environmental Science and International Studies and minors in Biology, French and Spanish. I longed to escape after I graduated, but I had already been accepted into a master’s degree program at the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies. I finished my senior honors thesis on “The Sustainable Development Paradox” the summer of 2002, and the following week I reported for two more years of intense classes at Yale.

I indulged my wandering heart for 10 weeks in the fall of 2004 after I finished my master’s, driving cross-country with my high-school sweetheart who would become my first husband, but it wasn’t the wilderness quest I’d imagined. We spent long days in the car driving from one national park to the next, viewing wildlife and scenery out the windshield in bumper-to-bumper traffic, then posting up for the night at a series of cheap motels watching MTV on cable. After 10 weeks and 10,000 miles, we returned home with empty bank accounts to live with our parents and find jobs. After that trip, I only made it two years in the so-called “real world” before returning to academia for my PhD, where I could live in the world of ideas instead of the world of offices and spreadsheets and 30-minute lunch breaks.

But after I’d survived another semester of the academic grind, more intense than anything that came before it, Chris McCandless had my attention. His parents had expected him to enroll in law school after he graduated Emory, but he had other plans. Alaska, the last frontier, called to him. Its whisper had become a roar, and he pursued his goal with single-minded fanaticism. He wanted to get as far away as he could from the weight of expectations—his parents’ and society’s—and live a free life, depending on nothing but the land. He fancied himself “AN AESTHETIC VOYAGER WHOSE HOME IS THE ROAD,” according to a personal manifesto he carved into a piece of wood. He even gave up his name, introducing himself to those he met in his travels as Alexander Supertramp, or just Alex. He had no address, no phone, no contact with his estranged family. His story was uncovered because Wayne Westerberg happened to turn on the radio and hear a report of a deceased young man discovered in the Alaskan bush. He suspected it was Alex, and he notified the authorities and told them what he knew.

Chris’ wilderness experiment wasn’t a failure. He hiked 20 miles along the Stampede Trail in spring snow, and forded the Teklanika River downstream from where I am now camped. He discovered the old Fairbanks city bus, which had been dragged into the backcountry in the 1960s and served as a stopover for hunters. It had a wood stove, a dusty mattress, and a bucket to collect water from the nearby river. Chris made this his base camp, and for the next two months he hunted small game, foraged wild plants, read Thoreau’s Walden, and explored the surrounding wilderness.

By July he felt satisfied with his experiment and his burgeoning survival skills and longed to return to civilization and regale his new friends with stories of his adventures. Chris packed his bag and hiked out the way he came. But runoff from the surrounding mountains had swollen the Teklanika River, and Chris didn’t dare cross the raging torrent. He returned to the bus to wait out the river and attempt the crossing again in a few weeks.

Unfortunately, game grew sparse in July and August. Chris relied more heavily on foraging plants he identified from a field guide, but it was difficult to tell some of the edible ones from the poisonous ones. He became gaunt, adding notches to cinch in his belt buckle with each passing week. He rationed the last of the bag of rice he’d packed in April. By August, he was starving to death, too weak to attempt escape.

On August 13, 1992, Chris pulled out his camera for a farewell self-portrait, holding a note he penned in all-capital block letters: “I HAVE HAD A HAPPY LIFE AND THANK THE LORD, GOODBYE AND MAY GOD BLESS ALL!” This was the last day he kept a journal. He marked the next five days with a number and a blank line, until he died in his sleeping bag and parka on the cot in the bus on Day 113: August 18, 1992.

It is now August 18, 2023, and I’m sitting in my van at the Teklanika Campground in Denali National Park, 15 miles upstream from where Chris crossed the river in April and failed to cross in July 1992. I am struck by the irony that his base camp at the end of the Stampede Trail was surrounded by national park land to the north, south, and west; that if he’d had a map of the area, he would have seen that he could follow the western bank of the Teklanika River and intersect the park road in just a day’s walk. He wasn’t that far into the wild. Just 15 miles due south of Chris’ base camp, tourists sporting Denali hats and t-shirts rode in tour buses back and forth along the park road, snapping pictures of moose and grizzly bears, then returning to posh hotels just outside the park’s gates to wine and dine and tell tales of their adventures.

Chris didn’t know this because he didn’t have a map. He didn’t know where he was, and probably didn’t want to know. It would have spoiled the romance of it, and his image of himself as a rugged pioneer exploring an unknown frontier.

For the past 31 years, many Alaskans have dismissed Chris McCandless’ life and death on the Stampede Trail. They see him as just another kook from the lower 48 who thought he could live off the land in one of the continent’s most harsh, unforgiving environments. They resent the hubris of an inexperienced outdoorsman going into the bush to hunt and forage, not knowing how to bag game or preserve meat or distinguish the poisonous berries from the edible ones. In Chris’ defense, he was learning by doing; he was a student of the land and its vicissitudes. He was following a dream, but more than that, he was pulled by a calling to shed the trappings of civilized life. According to his wood-carved manifesto, Chris viewed his Alaskan odyssey as “THE CLIMACTIC BATTLE TO KILL THE FALSE BEING WITHIN AND VICTORIOUSLY CONCLUDE THE SPIRITUAL REVOLUTION!”

To Alaskans, he may have been a yahoo, but in Chris’ mind, he was a revolutionary, journeying to Alaska to “to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life” as Henry David Thoreau had done nearly 150 years earlier on the shores of Walden Pond.

Like Chris’ Alaskan homestead, Thoreau’s Walden retreat was an imagined wilderness. Trains traveled the pond’s shore day and night, bringing people and goods back and forth to nearby Boston. Like Chris, Thoreau didn’t own his homestead; he was invited to stay there by his friend and literary mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson. But these two young men (Thoreau spent his 27th and 28th years at Walden) shared a philosophical and aesthetic idealism that made them both iconoclasts and icons, eschewing careers, money, and family for the call of the wild.

I’ve tried to read Walden a dozen times, since my days in my college dorm fantasizing about escape. At Yale I even took a course on “Wilderness in the American Mind” where it was assigned reading, but I barely made it through Thoreau’s dense and heady prose. The most I got out of the book was on an afternoon in July 2018 when I visited Walden Pond for the first time and sat on its crowded, sandy shores with the book in hand, then floated face-up, arms outstretched in the emerald water like I imagined Thoreau doing. “Fuck civilization,” I said to myself, surrounded by hundreds of fellow pilgrims and revelers.

I’ve brought a similar sense of idealism and irony on my road trip to Alaska. My pilgrimage to this wild place was inspired in no small part by Into the Wild, sharing Chris’ dream of getting as far away from society and expectations as possible, seeking solace and spiritual healing among the rugged mountains and forests. The film is the only movie I enjoy watching over and over again. I used to pull out the DVD on a second or third date when I was single to gauge my suitor’s reaction to the idea of living an unconventional life. Seth passed the test, and has since watched it another dozen times with me, in all the moments I yearned to sell my house and get rid of everything I owned and hit the road.

My departure for Alaska three weeks ago may not have been quite that dramatic—the house is rented on Airbnb, with my clothes still hanging in the closet and folded in the dresser—but I made it here after driving 5,000 miles alone in my camper van, and Seth flew in Sunday night for two weeks for our belated honeymoon. We spent our first two days together driving the remote Dalton Highway to the Arctic Circle and back, then headed south from Fairbanks for our camping reservations in Denali. As an afterthought on our drive, I turned on an audio tour of all the major Alaska highways that I’d downloaded to my phone before I left. It was the tour narrator who alerted me that we were about to drive past the fabled Stampede Trail; that the actual bus where Chris McCandless lived and died had been airlifted to a museum at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks (we had camped in a University parking lot the night before); and that the replica bus that Emile Hirsch inhabited while filming the movie had been donated to the 49th State Brewery in Healy, Alaska, a small town on our way to the park.

Seth and I peeled our eyes for signage to the Stampede Trail. We had just about given up and thought we’d missed it when I spotted a green street sign for Stampede Road, just like any street sign in any town in the U.S.. Ever the tourist, I jumped out to take a picture and then asked Seth to drive us to the end of the road, where according to my map, the Stampede Trail started. The road climbed on pavement and then gravel to about 2,500 feet in elevation, then turned into a four-wheel trail just south of Eight Mile Lake. It was drizzling now, but we hopped out of the van and took a few photos at the spot where I imagined Chris shouldering his rifle, donning his rubber boots, and waving goodbye to Jim Gallien. I wore my brand new black-and-teal t-shirt that said “I Crossed the Arctic Circle,” and smiled big with my arms outstretched.

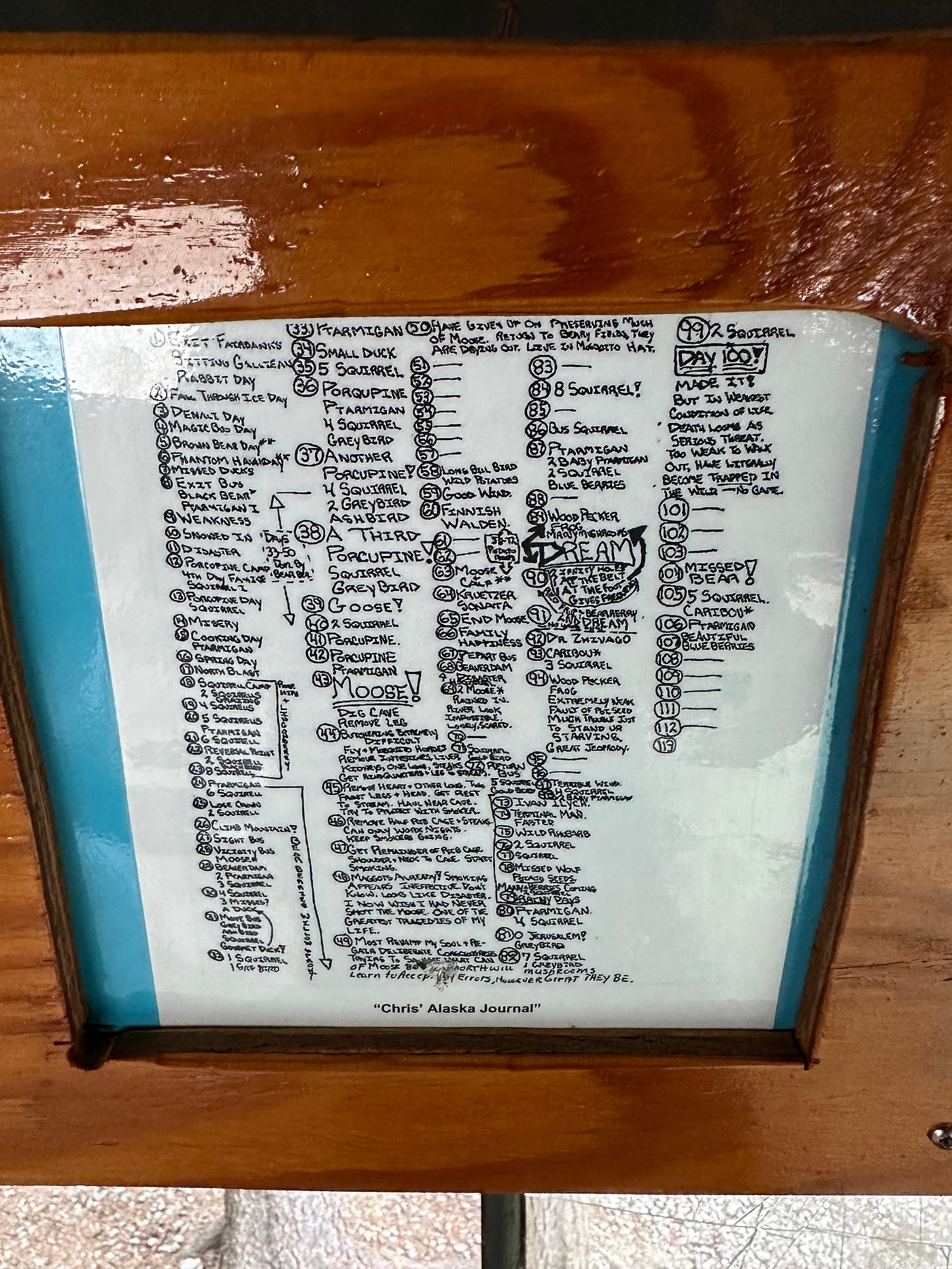

We repeated the ritual down the road at the brewery in Healy, where my breath caught in my chest as I walked through the wooden gates of the property and laid eyes on the rusty green Fairbanks city bus number 142. We were the only ones there when we arrived, and after a few snapshots of me outside the bus, stepping onto the bus, and peeking my head out the window of the bus, I took some time to reverently survey the interior. It was brown and rusty and dusty, with an “Enter at Your Own Risk” sign hanging from a chain on the door. I snapped a few photos. But I stopped in my tracks when I realized what this replica contained: ringing the walls of the bus was a timeline of Chris’ Alaskan adventure in his own words and images. Chris’ family had provided laminated photocopies of his hand-written notes, post-cards, and journals and the photos from his camera that were developed posthumously, outlining day by day his experience on the Stampede Trail.

The book and movie had included small snippets of these words and images, but here they were laid out in chronological order for me to drink in. Much of it was material I’d never seen before, even being a fairly fanatical fan of the story. As my eyes moved from one framed placard to the next, I hung on Chris’ every word and picture, from his hopeful yet foreboding missive to Wayne and his shotgun-shouldering departure image taken by Jim, to his self-portraits in and around the bus, pictures of the game he killed and berries he harvested, and the “DISASTER” of killing and failing to properly preserve a moose, which he described as “ONE OF THE GREATEST TRAGEDIES OF MY LIFE.”

On July 5th, after his failed attempt to leave, Chris wrote: “RAINED IN. RIVER LOOK IMPOSSIBLE. LONELY, SCARED.” His journal consisted of one-or-two-word entries on a single sheet of paper every day for 113 days. He recorded “DAY 100! MADE IT! BUT IN WORST CONDITION OF LIFE. DEATH LOOMS AS SERIOUS THREAT. TOO WEAK TO WALK OUT, HAVE LITERALLY BECOME TRAPPED IN THE WILD.—NO GAME.” Most of the next two weeks were marked with blank lines, indicating either that he’d found no food or had no energy to write. The final day, 113, is numbered expectantly, then left blank; no line, no last word.

In his days of desperation, Chris penned a letter for help: “ATTENTION POSSIBLE VISITORS. S.O.S. I NEED YOUR HELP. I AM INJURED, NEAR DEATH, AND TOO WEAK TO HIKE OUT OF HERE. I AM ALL ALONE, THIS IS NO JOKE. IN THE NAME OF GOD, PLEASE REMAIN TO SAVE ME. I AM OUT COLLECTING BERRIES CLOSE BY AND SHALL RETURN THIS EVENING. THANK YOU, CHRIS MCCANDLESS, AUGUST ?” This is the first time in his travels that Chris had used his real name.

Next in the display along the replica-bus wall was the photo of Chris smiling and waving goodbye, holding his block-lettered farewell message. Tears filled my eyes as I read this hand-scrawled note and saw the photo of the white teeth behind his gaunt smile, the wild hair, the acceptance of death that had come with his deep-dive into life. On the back side of the paper where he wrote his final goodbye was a poem by Robinson Jeffers, ripped from the pages of a book:

“Death’s a fierce meadowlark: but to die having made Something more equal to the centuries Than muscle and bone, is mostly to shed weakness. The mountains are dead stone, the people Admire or hate their stature, their insolent quietness, The mountains are not softened nor troubled And a few dead men’s thoughts have the same temper.”

And yet it is clear from Chris’ last words that he did not wish to die. In the Into the Wild book and the movie, the most memorable line was a note Chris scrawled in the margins of one of his books, perhaps around the time he decided to walk out of the wild in early July. It read: “HAPPINESS ONLY REAL WHEN SHARED.” In his ascetic experiment, Chris came to the realization that his spiritual wholeness required the company of others. He had found a sense of community and identity in the offbeat friends like Wayne Westerberg who had taken him in like family and loved and accepted him for who he was, in contrast to the parents whom Chris felt loved him only in their own image, for who they wanted him to be, admonishing him to repress his quirks and longings.

I hadn’t set out to be a pilgrim at the altar of Chris McCandless’ story, if only because my trip has been so rushed that I didn’t have time to plan or research how my journey might intersect his, and because I imagined he would have been in a place so remote I wouldn’t have access to it. I was amazed to pick up his trail just 8 miles off the highway on the way to Denali, and in the front yard of a brewery just north of the national park. Were it not for the serendipity of my last-minute audio tour, I’d have driven by and missed my chance to connect with the figure who most inspired my trip.

Before we left the bus at the brewery, I did as a sign suggested and pulled the rusty metal chair along the side of the bus, crossed my left leg over my right, put my hands on my lap, leaned my head back and smiled for the camera, reenacting Chris’ self-portrait when he discovered his new home on the banks of the Susitna River. I cringed at how kitschy this was, and how Chris would have scoffed at the idea of one person—let alone thousands of fans—coming to bow at the Mecca of his life and death. But I couldn’t help myself. There’s always that fan-girl flutter of the heart when we follow in the footsteps of our heroes. I was even more amazed when we arrived at our campsite a few hours later and I looked on the map, realizing it was on the banks of the same river that had sealed Chris McCandless’ fate; that if he had only walked here, he would have survived.

If Chris had managed to walk out of the Alaskan bush 31 years ago, he would be in his 50s now. I’d like to think that if he were alive today, he might be out here cruising around in an old van like me, reminiscing about the wild days of his youth. He might be the wild-haired guy at the next campsite, who I could join around a campfire and pick his brain for places to go and things to do.

But would I be here today, on the banks of the Teklanika River in Denali National Park, if Chris McCandless had not died? Would the embers of my Alaska dream have ignited so fiercely if not for the wanderlust and romance of his story? Would this landscape have burned into my brain had I not spent the past 15 years driving through mountain landscapes listening to Eddie Vedder’s Into the Wild soundtrack, singing along to the lyrics “Have no fear, for when I’m alone, I’ll be better off than I was before. I’ve got this light, I’ll be around to grow. I will always be better than before…” or “Society, you’re a crazy breed. I hope you’re not lonely without me…”

I know only this: I am here, and he is not. Through no effort of his own, Chris’ life inspired thousands—perhaps millions—through Krakauer’s storytelling to slough off the trappings of civilization and pursue their own authentic life, whether for a day, a weekend, a year, or for the rest of their time on Earth. His idealism and sense of adventure no doubt sparked the movement that is now #vanlife; the growing popularity of long-distance hiking and peak-bagging; the Millennial imperative to quit your day job and sell the story of your life on Instagram. Chris McCandless became a posthumous icon of how to live life outside society’s norms, much like his own idol, Henry David Thoreau. His story ended tragically, but it almost had to in order to spread his anti-establishment doctrine of simplicity. If he had walked out of the Alaskan bush alive, there would have been no book, no movie, no role model.

On our way out of the brewery as we walked away from the bus, I overheard some probably-already-several-beers-deep guy grumble about that stupid kid who drove this bus into the wilderness and got trapped and died. I have never punched anyone in my life, but I almost turned around and slugged the guy for his ignorance and irreverence at the altar of my hero. I didn’t turn to look at him, because I wasn’t sure I could hold my tongue, or my fist. I kind of wish I’d let him have it, at least verbally, and defended Chris’ memory and the outsized influence of his life and death.

I bet Chris would’ve gotten in a bar fight with the guy, and probably would have lost. But he won the philosophical argument by demonstrating the courage to live his ideals, even to his death. I think he’d be more than a little pleased that he inspired so many others to do the same.

Ahhhh man. This post gave me goosebumps and brought tears to the eyes. Like you, I feel such a passion for the story of Chris. I feel he was so beyond his timeline when it came to questioning and bucking against the norms of society. His authenticity, his determination to follow his heart and to live the path less walked moves me deeply. The book sits on my bookshelf, well-worn and heavily marked. Loved, loved, loved reading this. I feel like, in his short life, he lived with more soul then many live in a life of 90 years. 🥹

I’ve traveled to a few places Chris visited around America over the years but my trip to Alaska in 2002 changed my life. Long before I even got to Alaska I stayed at a campground Chris did, Laird Hot Springs in northern BC. This stop quite seriously changed the direction on my life for evermore.

I was Traveling with my dog Abbey who basically looked like Lassie. She wandered into the next campsite and started playing with the 2 kids there. Chasing the maybe 5 year old girl on her bike while her little brother ran behind. The parents made dinner and smiled as they watched their children play and that’s when I decided I wanted that. At that point in my life I’d been married 7 years and with my wife for 12. The next day as I stood at a pull out watching a moose swim a lake in Alaska on the way to Anchorage I called my wife and said “I’m ready” that’s all. She knew exactly what that meant and a year later almost to the day our first daughter was born.

Point being if it had not been for Chris’s story as told by Jon would I have ever sought out Laird Hot Springs and had this vision that changed my life? I guess we’ll never know but I’m giving him full marks for changing the direction of my life.