Bonding with a Beetle

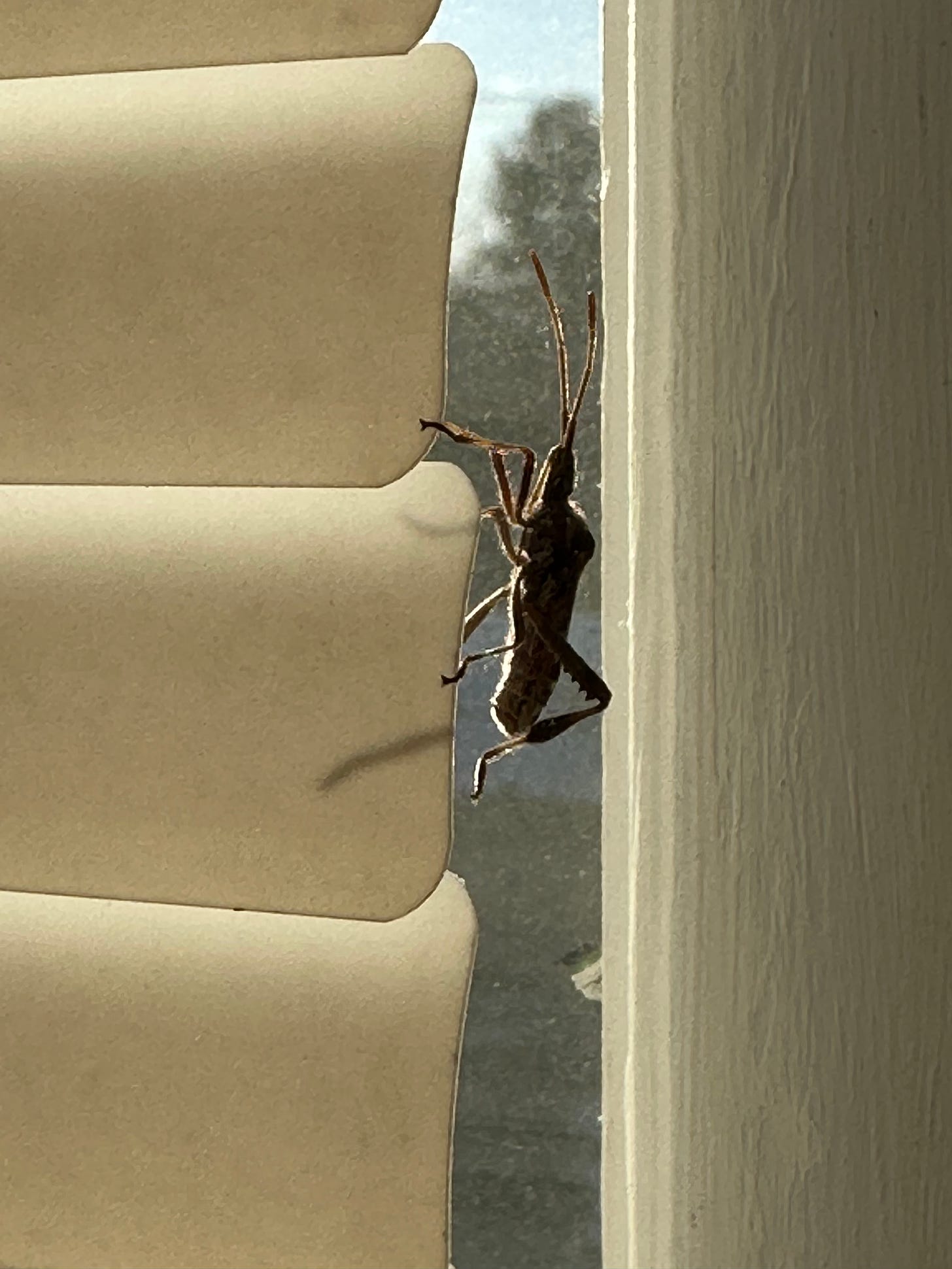

Meet my new friend!

A beetle took up residence in our bathroom this winter, and I named him Bond.

In January, Bond appeared on the window sill next to the toilet, then on the wall beside the mirror, then one time crawling up the shower curtain. He was brownish, with six legs and two long antennae that groped ahead of him like a blind person taps a cane. He crawled slowly, deliberately, like a cheetah stalking his prey.

I looked forward to seeing Bond, wondering where he’d be when I stumbled into the bathroom half-asleep every morning, and disappointed if he wasn’t there waiting for me. Then I started to look for him—especially after I found him crawling on the floor in front of the sink. I felt protective of my new housemate, and knew I would feel bereft if I accidentally squashed him while I was brushing my teeth.

One day I asked my husband what kind of beetle he thought this was, and he called it an assassin beetle. “What should we name him?” I asked, and then the answer came to me: Bond, James Bond. Because how many assassins could I think of besides 007? I will acknowledge my unconscious bias in assuming the beetle was a “he” (people often make that mistake with my female dogs, and it irritates me). But lacking any anatomical distinction to suggest otherwise, “he” is what I defaulted to.

Once Bond had a name, he stepped into his new persona like a spy shrugs on a black overcoat. His moves became increasingly stealthy and daredevil, and he seemed to seek me out. One morning when I pulled the bathroom scale out from behind a shelf, I found him attached to the edge of it, ambush-style. One evening I reached for the soap pump and after releasing it from my grasp, I found Bond crawling on the handle I’d just pressed. He watched me for a moment, then took flight and landed belly-up in the wet sink, his wings stuck to the wet spot where I’d just washed my hands. He kicked and struggled against the surface tension of that thin film of water, and after a moment I was afraid for him. Worried I’d pull a leg off if I picked him up, I instead grabbed my toothbrush from its holder and extended the tip of the handle to his six flailing legs. He was able to latch on and pull himself free. We rested for a moment, eye-to-eye, and let the adrenaline drain from our nervous systems. Then I carefully placed him on the curtain rod to dry.

After this bonding experience (pun intended), I started talking to Bond throughout the day, especially on the days when I didn’t see him. “Where are you, Bond? What are you up to today?” was our typical conversation. And I’ll be damned if he didn’t find a way to say hello to me later that day. He even started venturing outside the bathroom for a visit—crawling up the carpet on the stairs, or appearing on the bedroom wall as I was about to fall asleep. I was comforted by these visits, and it began to feel like we were really communicating, this bug and me.

Our intimacy grew deeper the night that Bond flew into my room at bedtime and landed on the rim of the water glass I was about to drink. This felt like a visit from a friend, and I paused to have a moment with him. I picked up the glass and brought him eye-to-eye with me, asking about his day. He had two black eyes the size of a pin head that sat at the top of his long, pointy snout. His brown wings had a checkered pattern and folded flat on his back the way that a pop-up card flattens to fit in an envelope. He slowly crawled off the glass and onto my hand, and the tips of his legs (are they feet?) stuck to my skin like Velcro and tickled with every step. We stayed like that for a good minute, this assassin beetle crawling across the top of my hand and up my arm, and I wondered a little too late what, exactly, he was known for assassinating. With me, he was as gentle as fairy dust, then he spread his wings and buzzed toward the ceiling to let me sleep.

I’ve known this kind of intimacy with pets before; when my dog Baxter was a puppy, I’d stay up half the night with her stretched belly-up on my lap, talking for hours as I caressed her bare pink skin. And I’m no stranger to insect invaders: spring brings a colony of ants to my kitchen; the sunny days of fall attract swarms of ladybugs through the cracks of old windows and doors; plump, translucent-white spiders colonize the back porch with their ever-expanding webs on those hot nights of summer. For the most part, my policy is to keep peace with all life forms and gently evict them from where they shouldn’t be to where it’s OK to be, usually somewhere outside. With the exception of the black house flies that swarm incessantly in the windows while I’m trying to work, or the mosquitoes that sneak in on warm nights and buzz around my head as I sleep, I never squish a bug. I mind my business as long as they mind theirs. Many of them, I figure, are doing me a favor: there would be a lot more mosquitoes sneaking through the back door if my fat white spiders weren’t lying in wait with their braided webs. As for the ladybugs, who can begrudge a beetle known to grant wishes?

Bond was doing no harm, and while I might have ushered him out the bathroom window on a warm summer night, to do so mid-winter would be a death sentence. In welcoming him in from the cold, I gained a new friend. And on these long winter days alone in the house, I could use the companionship.

As I grew attached to my new friend and anticipated his visits, I began to notice that most human fear creeping into my thoughts: What if something happens to him? What if I accidentally step on him or the dog eats him or he falls upside-down in the sink again and I’m not there to save him? What if he crawls into a dark corner and never wakes up but I keep talking to him, keep searching for him, nailing “Missing” signs to telephone poles and going on the local news to try to find my friend? What if he disappears on one of his dark missions and never returns?

I needed to know his expected life span, so I finally googled “assassin beetle.” The internet told me that Bond could live up to 8 months, which felt like a huge weight lifted—maybe he’ll make it to summer and get to fly out the window one day and travel the big wide world, smelling the grass and the leaves, flying high on a current of air and perching perfectly camouflaged on a tree limb. Until then, we could be buddies. I’d keep him company until it was time for him to travel.

Then a couple days went by and I didn’t see my friend. I called for him around the house, asking where he was and imploring him to come say hi. I started asking my husband if he’d seen Bond, and telling him to be extra careful walking around, just in case. He was beginning to think me delusional, wandering the house talking to my invisible bug friend.

A couple of days into Bond’s disappearance, I was sitting in my round chair by the bedroom window and had just pulled the blinds down to keep the afternoon sun out of my eyes as I read. I was startled by a loud buzzing sound coming from near the window pane. I glanced over once, then twice, and chalked it up to the ladybug crawling across the sill. But I couldnt’ shake the feeling that this was the same sound Bond made when he’d nose-dived from the soap pump into the sink, or lighted from my arm and flown to the ceiling. It was a loud, brisk buzz of wings flapping and crashing against the blinds. I looked again and saw it: Bond’s unmistakable silhouette, backlit by the sun, a shadow of a beetle crawling on the back side of my mini-blinds. Then the tip of a leg poked through a slat between the blinds, then an antenna, and in a moment my friend crawled out to say hello.

It was a blissful reunion, made more poignant by Bond’s prolonged absence. “Where have you been, buddy? What have you been up to? I’m so happy to see you!” I gushed. We looked at each other for a long while. He crawled from the blinds up the side of my water glass, and I carefully came eye-to-eye with him as I took a drink. For the first time, I noticed a long tube extended from his mouth that groped ahead of him along with his antennae, then folded and tucked hidden under his abdomen when not in use. A bit of internet sleuthing revealed this to be his proboscis, a mouth-part he used to “inject a lethal saliva that liquefies the insides of the prey, which are then sucked out.” Also, “large specimens should be handled with caution, if at all, because they sometimes defend themselves with a very painful stab from the proboscis” (according to Wikipedia).

Worried that Bond might slip into the depths of my water glass and drown when I wasn’t looking, but afraid to pick him up, I opened a drawer and grabbed a pair of scissors. I placed the finger-loop of the scissors beneath Bond as he balanced on the rim of my glass and let him crawl on, then I safely placed the scissors on the window sill with Bond perched on the orange handle. I went back to reading my book and Bond stayed there, sitting on the scissors, and we hung out together. When I returned that night after dinner, he was still there. I left him a dead house fly for a snack.

I checked on Bond the next morning and he was still where I’d left him, on the scissors on the window sill, and so was the fly. Maybe this is why I sometimes didn’t see him for days, I thought: he must be resting. When I returned in the late afternoon he was still there, except he’d crawled under the scissors and appeared to be on his back. Afraid he was stuck, I lifted the scissors and tried to nudge him upright. He waved a leg but didn’t move. I gently picked him up and his limp body fell to the floor, landing upside-down. I knew something was wrong. I scooped Bond up and cradled him in the palm of my hand. I talked to him in soothing voices. “No, no, no, what’s happening Bond? Are you OK? Don’t leave me!” But I knew it was too late.

A few of his legs made final twitches and then he lay motionless on my skin. I told him what a good little bug he was, I thanked him for being my friend and keeping me company, I told him I loved him. I said a prayer. I perched him on the tip of my thumb and walked him around the house one last time, like a king on his throne, surveying his domain. Then I brought him back upstairs and found him a final resting spot, in a miniature teal pottery bowl on my bookshelf. Perhaps he’d gotten too cold by the window and needed to thaw out and wake up, I thought, but I knew deep down he would still be there when I returned in a few hours. And he was.

As much as I’d dreaded the loss of my friend, I felt honored that he paid me one last visit and stayed there, close to me, holding onto his last thread of life until I returned and could hold him in the palm of my hand and say goodbye. I felt relief that I wouldn’t be roaming my hallways in grief, calling his name for days and weeks until I discerned the inevitable. I felt proud that I could honor him with his very own throne on my bookshelf, where he could look out the window and watch the sunset in his afterlife. I believed that he’d known me, and liked me, and chose to be with me in his final moments. I had, for the first time in my adult life, opened my heart to a bug.

Later that night, I was sitting at my computer downstairs when I noticed something moving across the desk in front of me: Bond?! It was the same species of assassin beetle, but upon closer inspection, this one was slightly bigger than Bond, and had only a stump where its left middle leg should have been. I rushed upstairs to check, and found the carapace of my dead friend lying where I’d left it. I headed back downstairs and introduced myself to the new, resurrected Bond: the Roger Moore to my Sean Connery. He charmed me by crawling onto the top edge of my laptop screen and perching himself atop my webcam, surveying his new domain.

My grief drained out of me as if pulling the plug on a sink, and I remembered: James Bond never dies.