An Unexpected Turn - Part 1

The Donor

“I'm coming for you, baby!” I exclaimed as I clicked on my blinker and turned my 1999 Roadtrek camper van east onto Highway 50, into Nevada’s Great Basin. I tapped both of my hands against the steering wheel for emphasis.

I had just spent an hour waiting in line for the RV dump at the Maverik gas station in Carson City, just down the mountain from Lake Tahoe, not knowing which direction I was going to go: north, towards Crater Lake and Vancouver, then Alaska and the Arctic Ocean, continuing my year-long road trip up the West Coast from Baja? Or east, towards my New Hampshire home, my husband, and the fertility clinic where we had finally matched with an egg donor, to try one more time to have a baby?

In the hour I’d spent in line behind a dozen other RVs waiting to empty our septic tanks on Memorial Day, I had to make the biggest decision of my life. I’d had a month to think about it—ever since that day in the Mojave Desert when egg donor #1111234 had popped into my inbox, and I’d texted Seth to tell him that she was The One.

She looked like me: blonde hair, blue eyes, tall and big-boned, with similar features. She was hard-working, outdoorsy, and loved animals. She had a clean family health history. She adored her young step-children and wanted to help another couple achieve their dream of parenthood. I loved her instantly, and felt a connection that had eluded me in the two years we’d been watching donor profiles land in our inbox. Plus, her donor number seemed to be a sign: my whole life, I’ve made wishes when the clock hits 11:11 or 12:34. How could this not be cosmically ordained?

That first week of May when I discovered our donor, I had been camped alone in my van in the middle of the Mojave, along the trail to Banshee Canyon, surrounded by desert mountains and ancient petroglyphs. I’d needed a place to regroup after two and a half months traveling Mexico’s Baja peninsula, followed by several weeks in Arizona getting solar panels installed on my van. The plan was to continue up the West Coast, catching a ferry in June from the northern tip of Vancouver that would transport my dogs and me to the island of Haida Gwaii off of northern British Columbia, then drive up the Cassiar and Dempster Highways through the Yukon and Northwest Territories to the Arctic Ocean at Tuktoyaktuk. I had conceived of the journey two years ago, when I bought my van and traveled solo to Alaska after our first round of fertility treatments failed. In the intervening year, I had returned home from that trip and spent a year trying to adopt from foster care, enduring more heartbreak. When our case worker left her job last fall and left our adoption hopes in limbo, I’d gotten back on the road, spending the winter exploring Baja and the national parks of the American West while I healed my grief (again) and decided what to do next.

I’d been on the road nearly six months, sleeping under some of the darkest night skies in North America, studying the saguaro and cholla and cardón cacti of the western deserts, and strolling the white-sand beaches of Baja while I also fielded phone calls from the fertility clinic and filed paperwork for our foster relicensing. The parenthood question never strayed far from my mind, and if it did, it came rushing back when a Mexican girl smiled at me with her brown eyes as I jogged past the playground in Mulegé; when I listened to a family of four giggle around the campfire in Joshua Tree National Park; or when I watched a linen-clad, modelesque couple pull up to the brew pub in Baja in their sparkling white Mercedes Sprinter van and emerge with a cherub-cheeked toddler and a stroller. In taking this trip, I’d hoped to have a break from the relentless pressure of the past five years, wondering every day if or when or how I would become a parent. But the decision, and the reminders, followed me wherever I roamed.

So I notarized the paperwork for the foster agency as I passed through Roswell, New Mexico en route to the International UFO Museum; I had a video call with the donor coordinator at our local fertility clinic after snorkeling in the spring at Balmorhea State Park in Texas; I did a telehealth appointment with the Maternal Fetal Medicine specialist as I stared down the iron rungs of the Mexico border wall at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument; and after a day exploring the slot canyon and petroglyphs in the heart of the Mojave National Preserve of Southern California, I sat in my camp chair researching an embryo donation program in Sacramento that guaranteed success or your money back.

The Sacramento clinic sent me back down the fertility rabbit-hole, because I realized I was in California already, and what if I could just stop on my way north, run some tests, and pay $20K to have them pop a donated embryo into my uterus? I could hang out in my van for a couple months while I waited for the IVF procedure, eliminating the added expense of flights and hotels and car rentals if I’d had to travel back and forth from New Hampshire. Surely I’d be pregnant by fall and could drive home and have my baby?

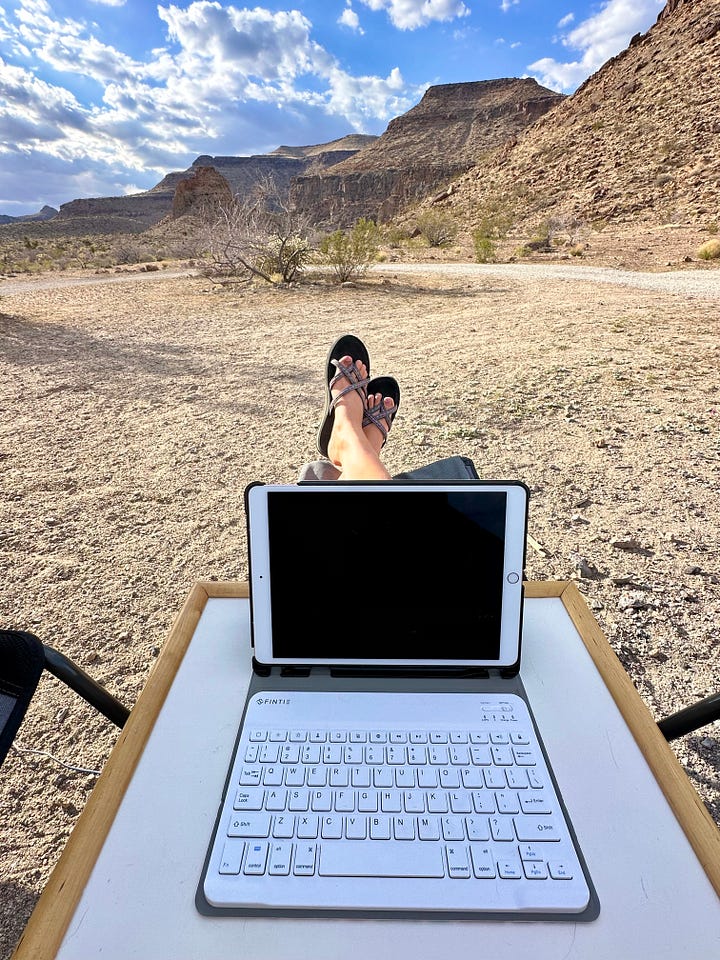

I cranked out the awning on my van in the middle of the Mojave and set up in the shade, cell phone in hand and Starlink connected, while free-range cattle wandered through camp and distracted my dogs. A bit of research revealed that this clinic didn’t have the best ratings; people had waited a year or more to receive an embryo, and they weren’t typical donor embryos (the kind left over from a prior couple’s IVF treatment); they were embryos created at random from donor eggs and donor sperm for the purposes of the program. People said it felt like a baby-mill, and communication and empathy were lacking from the staff. There were stipulations for the money-back guarantee. By the time I cranked in the awning and climbed back into the van for the night, I had given up on that idea, but I felt determined to find another solution. Then I remembered the egg donor back in New England who had arrived in my inbox, and I opened the email and found our match.

Whereas a donor-embryo baby would not share any DNA with my husband or me, doing in-vitro fertilization (IVF) with a donor egg would allow us to use my husband’s sperm. He would be the biological parent, and I would be the gestational parent. The process was considerably more expensive, but it seemed worth it to have more control over the donor-selection process and maintain some genetic connection. Having given up all hope for my aging ovaries after my 45th birthday, I had accepted donor conception as our next best option to have a baby.

As stars filled the desert sky, I lay in bed in the back of my van reading donor #1111234’s profile, and my heart expanded. For the first time in years, I felt something akin to hope—that a healthy egg would lead to a healthy pregnancy; that I could be spared the grief of more miscarriages or unsuccessful fertility treatments; that this baby would look like us and deepen the roots of Seth’s family tree. With our foster relicensing held up for months by the staff turnover at the state agency, and after the challenges we faced trying to adopt children with significant trauma, a donor-egg pregnancy seemed like the best way forward.

Over the next few days as I migrated from the Mojave to a campsite at 4,000 feet in the Panamint mountains of Death Valley National Park, I contacted the coordinator to claim our donor, set up the medical tests I’d need to proceed, spoke to the financial navigator at our fertility clinic, and secured support from Seth’s parents (as an only child, he’s their one chance at having grandchildren, so they deemed it a worthwhile investment). I felt happier than I’d been in a long time, with the realization that I would finally be part of the parenthood club that had eluded me for so many years. I was finally allowed to fantasize about my child splashing in the waves at the beach in Maine where I spent my summers vacations; taking a running leap off the dock at my in-laws’ lake house; dressing her in a cute little apron and mixing dough for cookies or soft pretzels; filling closets and drawers full of tiny little clothes; hearing the words “Mama” and “Dada” for the first time; choosing a name!

The fact that we could spend all this money and go through all this treatment and it still might not work was not something I allowed into my consciousness. As with all fertility treatments, there are no guarantees (even those that guarantee a pregnancy or your money back can’t promise a baby in your arms). The donor might not produce enough eggs, or her eggs might not be healthy (and that was assuming she didn’t change her mind about donating). The embryos might not divide properly in their Petri dish, or the blastocyst might not burrow into the lining of my uterus. My body might reject the fertility medications, or if I did become pregnant, I could miscarry again. There could be complications with the pregnancy—at 45, I would have a significantly higher risk of gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and maternal mortality. And for the tens of thousands of dollars we spent, we would only have as many chances as we had embryos—maybe one, maybe three, maybe five or six (luckily our clinic guarantees you at least one embryo, or they will cover the cost of another egg retrieval).

I told Seth that we were not allowed to talk about all the “what ifs”; that if we were going to do this, I needed to believe that it would work—that I was signing up to have a baby, not to go through more months of uncertainty, loss, and heartbreak. I knew of women who’d put the last of their hope and their money into donor conception and it hadn’t worked. I had to convince myself that that would not be me.

With this new turn of events, suddenly my road trip was in limbo. I drove through Badwater Basin in Death Valley on an unseasonably mild day, marveling at the vast salt flat surrounded by mountains, and trail-running through the painted hills of Artist’s Palette after a rare desert rainstorm. When the heat returned the next day, I retreated to the mountains, hiking 9,000-foot Wildrose Peak. I holed up in my van at a free campground frequented by wild burros, enjoying the 70-degree breeze on days that hit triple-digits in the valley. The fertility clinic sent a message saying that our donor was a genetic match—she and Seth did not share any genes that could transmit rare diseases to an offspring. Now we were just waiting to confirm her availability to donate.

I didn’t want to turn east until I knew the donor was a sure thing. If the match fell through, I thought, at least if I kept migrating north I could still catch my British Columbia ferry. And if she wasn’t available until fall, maybe I could make it to Alaska and back before starting my family?

I returned to the valley part of Death Valley National Park to dump my RV tank, and when I set my thermometer on the dirt, it registered 140 degrees. I needed to get moving.

I drove west out of the park, from an elevation below sea level to nearly 4,000 feet at Lone Pine, California. I camped in the Alabama Hills off Movie Road, a desolate landscape of rock formations where movies like The Lone Ranger and Star Trek were filmed. I caught my first glimpse of the snow-capped Sierras and Mount Whitney, the highest peak in the continental United States. The radiator in my van overheated as I drove to 8,000 feet on the Whitney Portal Road, but after giving the engine a break for an hour, I made it to the trailhead for Lone Pine Lake. This glacial tarn lay covered in ice and surrounded by snow-capped granite peaks, yet I could sit on its slope and see the hundred-degree Nevada desert below. I stood alongside streams of snowmelt cascading down the valley, the first running water I’d seen in six months, inhaling the damp moss and listening to water cascade over rocks. It stirred something in me, part primal instinct, part nostalgia for the woods and waters of my New England home.

On Mother’s Day, I parked at a gas station overlooking Mount Whitney and called my mom while I debated my next move. Snow shimmered on the crest of the Sierra while I holed up in my van with the air conditioning on. I had planned to work my way north along the eastern Sierras, but the town of Mammoth Lakes was forecast to dip into the 20s overnight, and I didn’t want to freeze my pipes. I’d also hoped to visit the Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest in California’s White Mountains, but after my radiator trouble ascending Whitney Portal and the acrid smell of brakes on the long descent, I thought it unwise to push the van to 10,000 feet where the bristlecones grew. When I hung up the phone with Mom, I deliberated for an hour. My only option to avoid the freezing temperatures of Mammoth and the elevation of the bristlecone forest was to head south and west in a windstorm towards Bakersfield. I would loop around the southern tip of the Sierras towards Sequoia, Kings Canyon, and Yosemite.

This would buy me time, I figured; a few weeks of sightseeing and a leisurely drift in the general direction of Alaska while I waited for all the fertility pieces to fall into place.

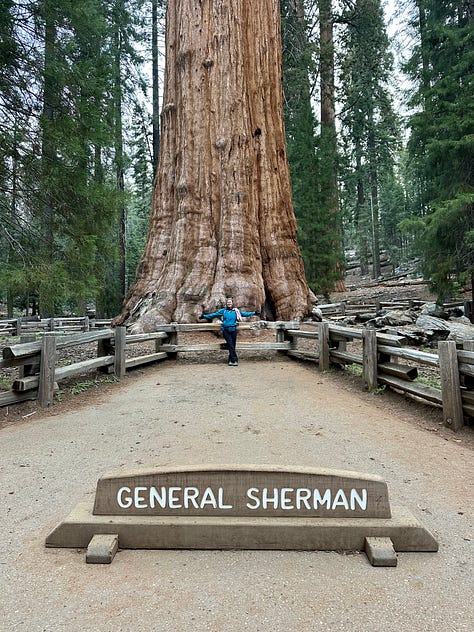

After a sweaty night sleeping in my van parked at Planet Fitness in Bakersfield, I crossed the Sierra foothills into Sequoia National Park and spent a day among the largest living organisms on Earth. The sequoias might not be as ancient as the bristlecones, but many of them were alive before Jesus and the Buddha. The scale of their colossal trunks looks comical compared to the surrounding incense-cedar, red fir, and ponderosa pine (which themselves are bigger than any tree I’ve encountered back East). I pictured my child’s hand pressed against the furrowed red sequoia bark, and imagined her picking up their egg-shaped cones that contain seeds capable of outliving civilizations.

A few days later, I was camped along the roiling Kings River when I got word that our donor was available for an egg retrieval in June or July. I had just spent the day hiking alongside the South Fork of the river to Mist Falls, sandwiched between the granite walls of Kings Canyon. This was the moment it finally felt real—this woman, that very week, had undergone a psychiatric consultation and genetic counseling in preparation to harvest her eggs for me. Now all I had to do was pay an astronomical amount of money and those seeds of human conception would be mine.

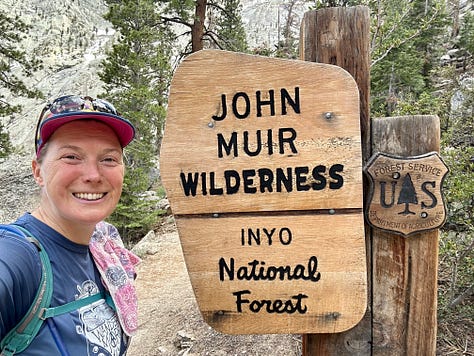

It was the moment of certainty I’d been waiting for, but my celebration felt muted. Now that this could really, truly happen—I could go home and become a mom—was it still what I wanted? Spending time in the Sierras stirred something inside of me—the towering trees, the granite cliffs, the starry skies, and the roaring rapids right outside my window—this felt like home. Returning to a wet, green environment after so many months dried up in the desert expanded me like one of those plastic capsules that turns into a foam dinosaur when soaked in a bowl of water. This expansion complicated the resolve I’d felt in the Mojave to go home and have a baby. Now I could see myself backpacking the 210-mile John Muir Trail, summiting 14,505-foot Mount Whitney and her surrounding peaks. I could imagine living in the national parks for months on end, falling asleep to the smell of campfire smoke and a thousand stars shining through my window. I could picture going back and forth between Baja and Alaska and exploring everywhere in between, for the rest of my life.

And yet, all along, I’d hoped to do those things with my kids. As I’d strolled through Sentinel Campground in Kings Canyon, I’d watched the families around the campfire, finally allowed to think that it could be me. Instead of skulking alone in the dark with my dogs, I could be smiling at glowing faces covered in marshmallow goo and graham cracker crumbs, laughing and telling stories. It felt complete. It felt right.

I held that image as I continued north to Yosemite, counting down the days before that final turning point at Tahoe, where I would either go east and forsake Alaska or continue north and forsake parenthood. It felt like it was now or never—THIS was the time, THIS was the donor, and if I didn’t act, it would slip through my fingers.

There were many reasons for my sense of urgency. Seth and I would already be 46 by the time the baby came, and our parents are approaching 80. Every month made a difference. I hoped to time the birth for the following summer, when my in-laws visit their New Hampshire lake house. If I waited a few more months to conceive, they would be on their way home to Ohio by the time the baby came. And it already felt uncertain whether all four of our parents would be well enough to enjoy a grandbaby in a year’s time.

I also feared that if I didn’t claim this donor, someone else would, and I’d lose out on our opportunity. I hadn’t had the energy to explore national donor databases (which are more expensive) or switch clinics in search of the right match, and the donor pool at our clinic is small. I’d waited years for the right one to come along. What if she changed her mind, or her life shifted in a way that wasn’t conducive to a month of hormone injections?

There was the money factor—spending a summer in Alaska would draw down our savings, and a shift in circumstances could impact our family support. Seth’s or my physical health could change at any time with an unexpected diagnosis (a mammogram is a prerequisite for fertility treatments over age 40, as well as a uterine ultrasound). I couldn’t justify waiting, even if it meant missing my dreamed-of return to Alaska.

I also realized that my resolve for driving another 15,000 miles to the Arctic Circle and back was waning. I’d been living alone in my camper for six months. I’d only seen my husband once, for two weeks. The roads in Baja had wrecked my van, and I was wary of spending several more months driving teeth-chattering washboard and dodging potholes.

I was tired, and a little homesick. I had left New Hampshire on the cusp of winter, those gray and brown days of late November. Now in May I knew that leaves were bursting from buds, flowers were blooming, and it was warm enough to sit outside. This would be the summer of my mom’s 80th birthday and my parents’ 60th wedding anniversary. It would be the summer of my friend Anne’s long-awaited baby shower and the birth of her son after years of her own infertility, and my friend Erik’s long-awaited wedding to the man of his dreams. I missed my friends and family. I missed sleeping in a bed that wasn’t made of couch cushions. I missed having a shower that I didn’t have to set up and take apart and wonder if I’d run out of water mid-suds.

Giving up Alaska and going home felt surprisingly right, even after years dreaming of living on the road and my persistent urgency to escape my life. I could spend my summer in our retired 1991 Winnebago at Seth’s parents’ lake house, writing about my adventures from the comfort of our outdoor living room. I could swim and paddle and finally ride my bike again. I could get my teeth cleaned and my hair cut and have my annual physical. I could take Baxter and Laney for off-leash hikes without having to worry about them stepping on cacti or messing with rattlesnakes. Best of all, I could wake up in the morning and not have to wonder where I was or worry about where I was going.

As the month of May passed by, Alaska felt more distant even as I drove north. I traveled slowly, spending days in each of the Sierra national parks while I contemplated my future. When I arrived in Yosemite, I booked three nights in a campground at the base of Half Dome, thanks to someone’s last-minute cancellation. I knew this was my last stop before making The Ultimate Decision, and I lingered as long as I could.

Yosemite was packed: every campsite was reserved six months out, and every parking spot was filled by 8am. It was the week before Memorial Day. I drove up to Glacier Point to escape the valley heat and bugs, jockeying my way between tourists to take my picture with the rounded gray cliff of Half Dome in the background. The next day, I joined a parade of hikers to Vernal and Nevada Falls, leaving later in the day so that more of them were going down than climbing up. I was rewarded at the end of the day with a waterfall rainbow all to myself.

I wanted more.

I observed parents and families like an anthropologist observes a primitive culture. What were they thinking and feeling? Were they having fun, or stressed out? Were the tweens and teens that swarmed the campground charming or annoying? I studied the face of a dad backpacking up the start of the John Muir Trail to Little Yosemite Valley with his young son and daughter. Were the kids having fun? Was he? I imagined him studying my dogs and me, wistful for the days when he used to run mountains.

From moment to moment, I wavered in my commitment to pursuing parenthood. Moms and dads 10 or 15 years younger than me walked by wearing baby backpacks. I imagined they had been up since 5am entertaining and soothing their child. I knew they wouldn’t be hiking the ten miles I had just done after sleeping until 9am. Was I willing to trade this life for that one?

A little boy at Glacier Point helped make up my mind. He toddled around outside the visitors center, alert and curious with his bright blue eyes, giggling with his mom and dad. He locked eyes with me and smiled. I wanted him to be mine.

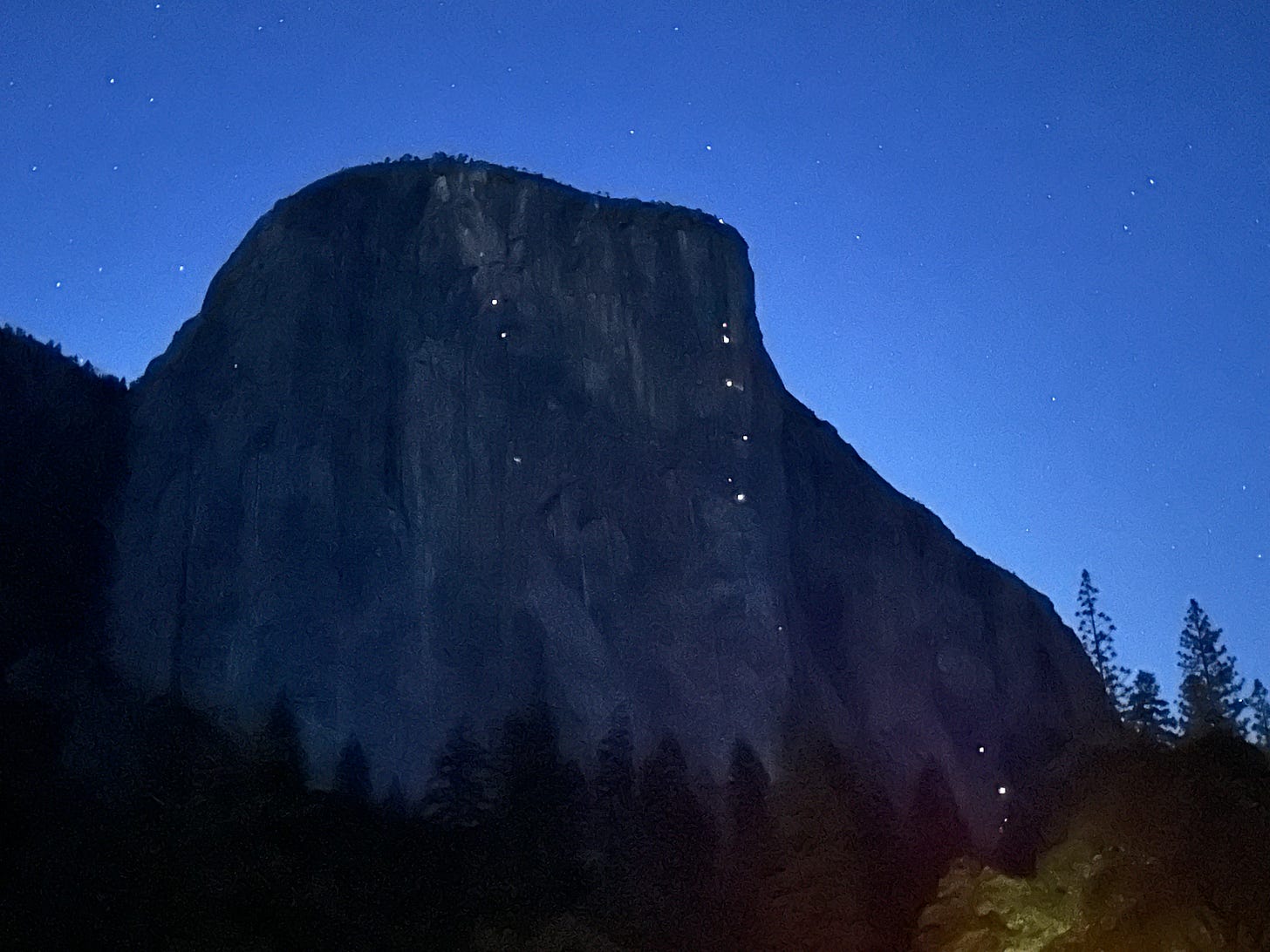

“I’m coming home!” I announced to Seth that night as I drove down into the valley. He had been vacillating with me about the decision, but said he would support whatever I wanted to do. I pulled the van over in the shadow of El Capitan, the 3,000-foot vertical cliff that Alex Honnold famously “free-soloed”—climbing the sheer granite face unassisted, without a rope or harness, in less than four hours (a climb that normally takes four to six days). As dark descended on the valley, climbers’ headlamps illuminated like a constellation of stars up and down the rock face, forming vertical patterns along cracks where they would hang hammocks and bivouac for the night. Seth asked if I was sure, and I told him about the little boy with the blue eyes. On my last night in Yosemite, I had made a decision. I was going to be a mom!

To celebrate the occasion, I jockeyed for parking at the park gift shop the next day so I could buy a Yosemite shirt for my baby as a token of my commitment. They were sold-out of onesies, but I found a green toddler t-shirt with moose, owl, and bear on it that said “Greetings from Yosemite.” I folded it and tucked it away in my clothes cabinet in the van.

I slept outside Sacramento the next night, in the parking lot of a Planet Fitness in Folsom, California, after purchasing a bottle of prenatal vitamins at the Sprouts Farmers Market next to the gym. On the outskirts of the town whose fertility clinic had sparked this turn of events, I called Seth on a Saturday morning and talked until the thermometer in my van topped 90 degrees. It was my last chance to change my mind and head north, and I still felt deeply ambivalent, despite my resolve at the base of El Capitan. Exhausted by the heat and the rehashing of all the same points, I decided to drive two hours to Tahoe before I made up my mind for sure. From there, I could either head east on Route 50 or continue north through Oregon and Washington to my Vancouver Island ferry.

This is how I found myself in Carson City on the Monday of Memorial Day, still debating my fate as I waited to dump my black tank at the gas station. Even after I’d finished the dump, I dragged my feet. I parked to let the dogs out, have another snack, and explore possible routes. It was already 5pm and I had to get on the move and figure out where I was sleeping—western Nevada, or Northern California?

When Seth called, I told him I was not ready to abandon the possibility of getting to Alaska this summer, and I thought I would continue north for a few more days while I made up my mind about the baby thing. But after spending another hour lying in the bed in the back of the van researching a route through some of northern California’s national parks, I felt my energy drain. If I was committed to parenthood, I couldn’t spend tens of hours and hundreds of miles driving in the other direction.

Frustrated and exasperated, I swiped out of my maps app and into Facebook for my daily hit of baby videos. I found it hard to articulate why, at 45, I still wanted a child after five miscarriages and multiple failed adoption placements. I could articulate a million reasons why diving back into fertility treatments and trying to have a baby at my age was a terrible idea. My logical brain couldn’t counter those arguments. Only my heart could, and it spoke when I watched those reels of newborns scrunching against their mom’s chest or letting out a big yawn and stretch, or a baby smiling at her mama and giggling.

Making a decision about anything in life based on how it looks on Facebook is probably a terrible idea, but that’s all it took. I put the van in gear, pulled out of the gas station, and turned left onto Highway 50, America’s Loneliest Road.

TO BE CONTINUED….

COMING SOON: PART 2 - THE DOUBT…

My dear readers, please refrain from congratulating me in the comments until you’ve read all three parts of this series. Thank you!

I think between you and Tom Ryan, I will see so much of the fabulous and interesting places of the United States. One of my top trips with my son and family was our trip to Yosemite in 2014 … growing up in NH and now living in OH, it was beyond anything I’d ever seen.

I always enjoy reading your posts …

I loved your Part 1. I'm looking forward to the others. Great story and I especially loved the pictures. It certainly brings back old memories when ex and I drove the US every year on vacation. That's one thing I miss about ex. LOL. The gypsy blood is still here I know now. Let us know how things go with your decision. I can understand ambivalence. Such a big decision. Good luck to you and hubby in whichever path you decide to take. If you decide to continue to travel, contact me and we can do the same. I certainly miss those days. Ha!